Grief

My mom passed away two weeks ago after a 10-year journey with Alzheimer's.

I'm sad. Looking at her face makes me cry.

I'm also sad about COVID deaths and George Floyd's homicide. (Indeed, the world is especially full of death right now.)

In today's article, I want to explore these deaths and my grief around them. I hope it helps you understand and work through your own grief.

I. The Death of My Mother

Here is the (zoom) eulogy I gave for my mom:

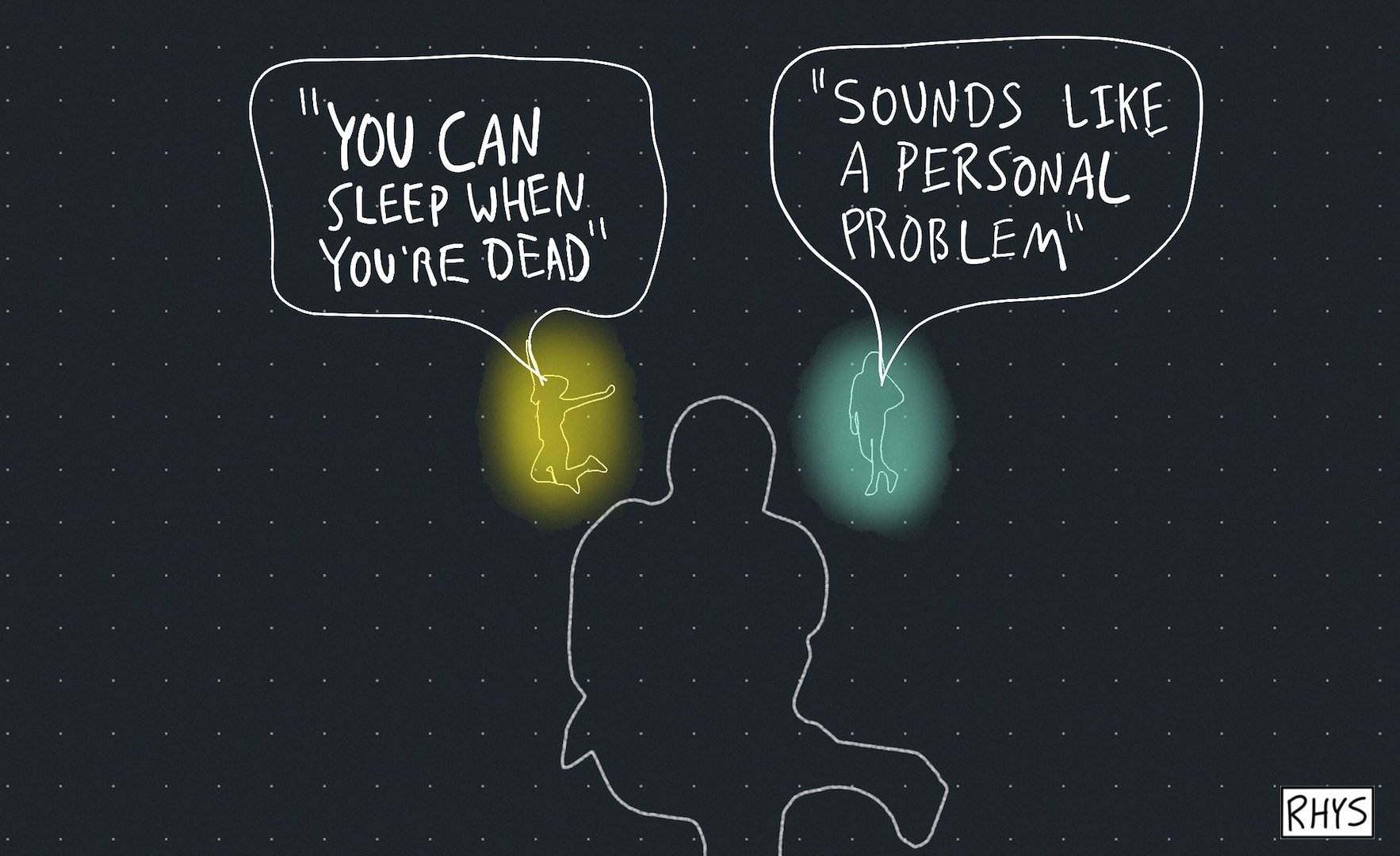

It's difficult to capture my mom's life in a few minutes. Today, I want to focus on a specific aspect of my mom—her language. She had a variety of unique phrases that we called "Mom-isms". I have a document full of these on my computer. I want to share two of them with you today.

The first Mom-ism (that was in her obituary) is: "You can sleep when you’re dead.” I understand this is awkward at her memorial. Because, well, she is dead. She’s sleeping.

While she was alive, what did this quip mean to her? To live a full life. Or, as she would say, “to pack it in.”

Many of you saw this first-hand. For friends in Denver: you know that her and my dad were the last ones to arrive at a party ("fashionably late”), but also the last ones to leave (you had to kick them out). Or with her friends in the meeting industry: you know she’d spend a week working long days organizing the event, and then spend the nights partying with her clients and co-worker friends.

It’s incredibly sad that she died at 67, with Alzheimer’s for the last 10 years. And at the same time, I’m grateful that she did live a life that was “always on”.

We never know when death will come for any of us.

So the next time you’re thinking “eh, should I call that childhood friend or spend extra effort on a work project”, have Christine on your shoulder, in your ear, saying “You can sleep when you’re dead”.

She’d want us all to say yes to things.

The second Mom-ism is “that sounds like a personal problem to me.”

What does this mean?

Part of it is the “problem" side. She's saying: “It’s fine. Life is full of problems. Got it, you have one too. Oh, I’m so sorry. Welcome to the club. We all got problems.” (Or as she would say, “issues.”)

Part of it is the “personal" side. She's saying, “It might be you. You’re a bit weird. You might be the problem.”

This was deeply loving in a counterintuitive way. Generally speaking, people want to be supported when they have a problem. But my mom had this amazing way to say: “Yeah, you’re weird.”

It’s not: "you’re weird and no one loves you." More like: “I’ll love you and always love you. And also you’re weird. That’s ok."

This takes a ton of emotional intelligence. There’s this view of my mom as an easygoing woman. That’s true, but behind the veil she has this amazing understanding of human nature.

Exposing our vulnerabilities is scary. But it was never really scary with her. She understood you, quickly and well. But instead of exploiting her understanding, she instead helped us all take a lighter approach to the human experience.

So again, when you’re complaining about something. Or maybe have a legitimate problem or personal vulnerability. Have Christine on your shoulder, whispering in your ear: “that sounds like a personal problem to me.” And you’ll be able to take a lighter view of life.

Those are two specific Mom-isms, but actually when you zoom out, every word I’m speaking now is deeply influenced by her. By you, Mom. From my tone to my cadence to my hand gestures. It’s all influenced by you. In me and in all of us on this call.

Many eulogies say that "the person will still be with us." Often, this means specific things, like a love of games or the outdoors. Language is this at a foundational level.

Mom, you gave us language. The symbols for communication. A deep sense of how we perceive and help others perceive the world.

So, I wish you weren’t dead, but you are. I wish you didn’t have Alzheimer’s, but you did. I wish that you could grow old with dad, or be a snarky grandmother to my kids.

But you can’t.

Still, I’m grateful that you raised me. I’m grateful that you helped build this beautiful group of people.

So yes, “you can sleep when you’re dead!” Live. Live now. Live fully.

And yes, "we all have personal problems!" We all got issues. We’re all weird. That’s ok.

And yes, thank you for your language and the lens you’ve given all of us. We all see the world through your eyes.

We love you and will miss you deeply every day.

II. What is Grief?

I was (and am) grieving my mother's death. But what is grief? And how does it relate to sadness?

Sadness is Simple: It Is Loss

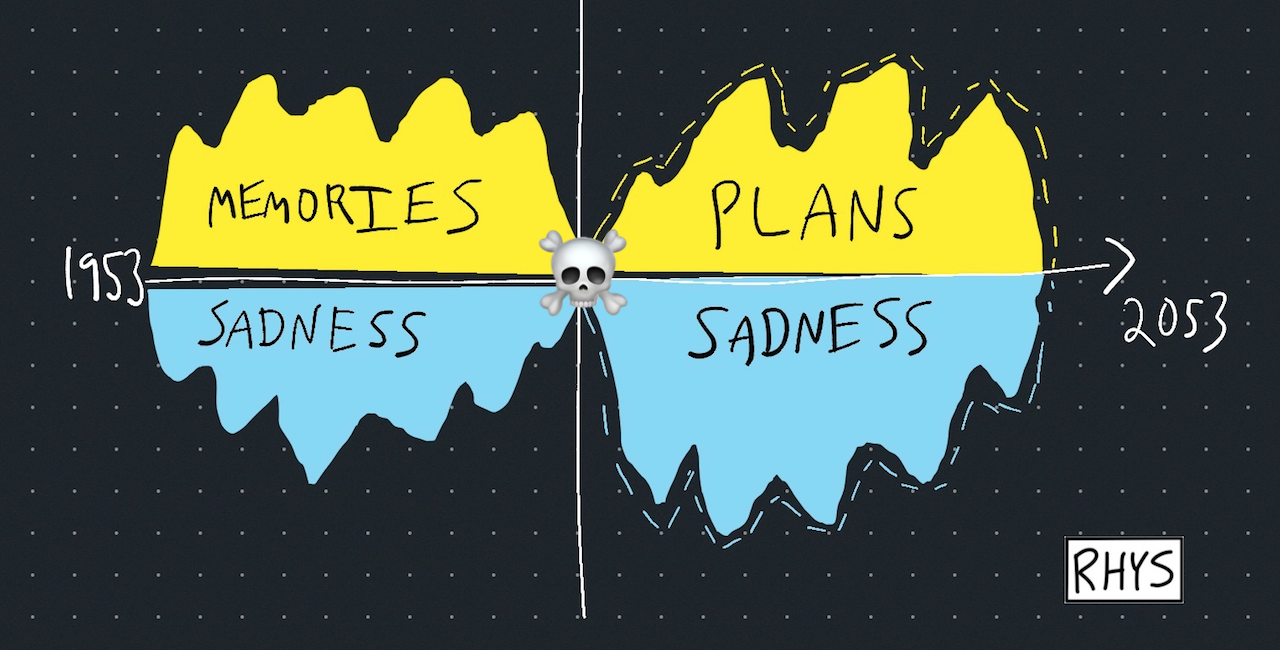

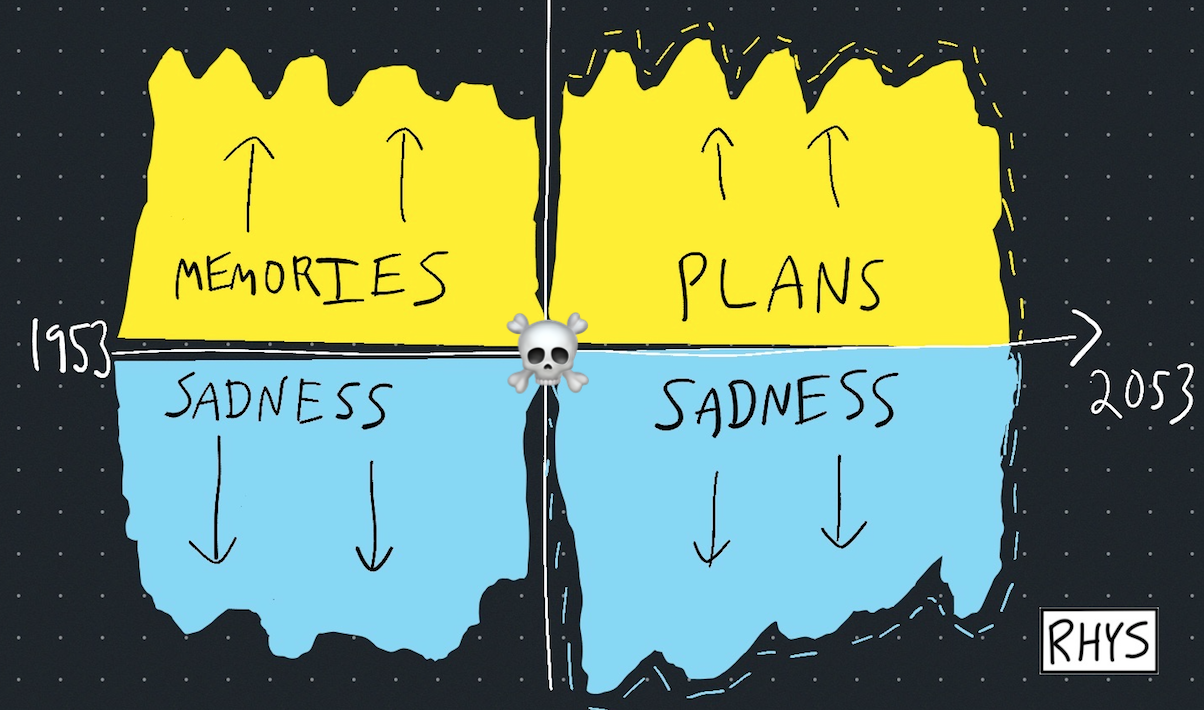

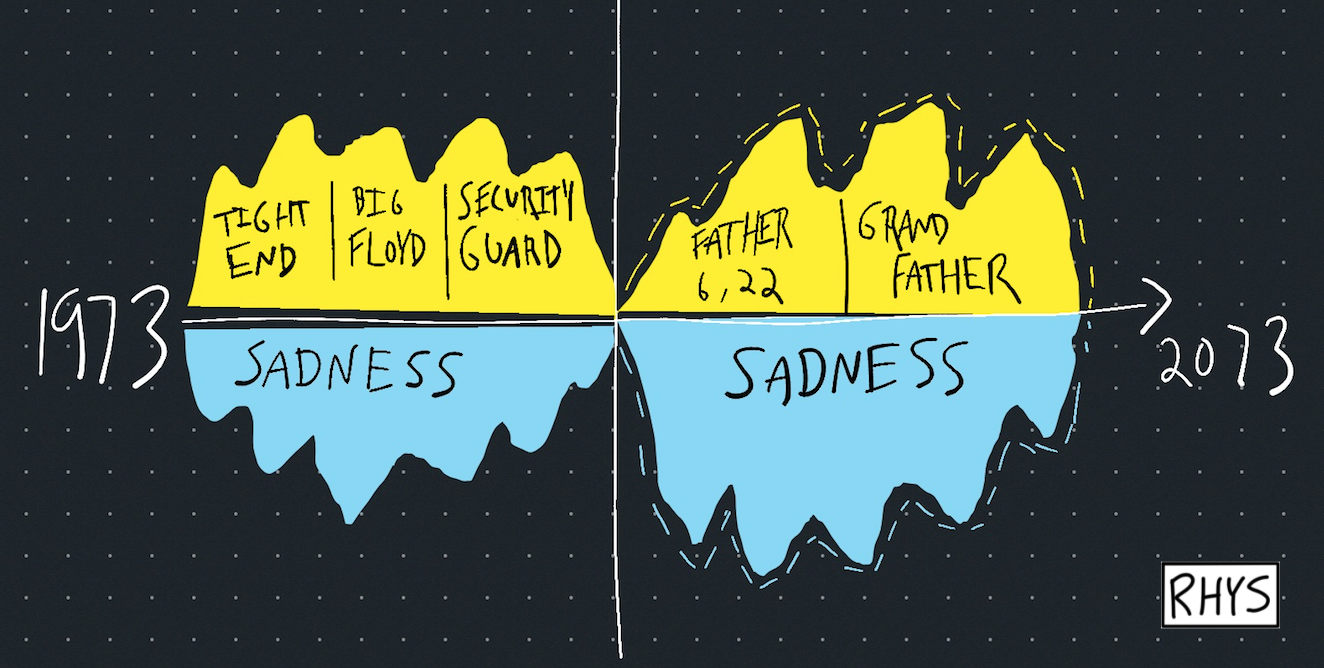

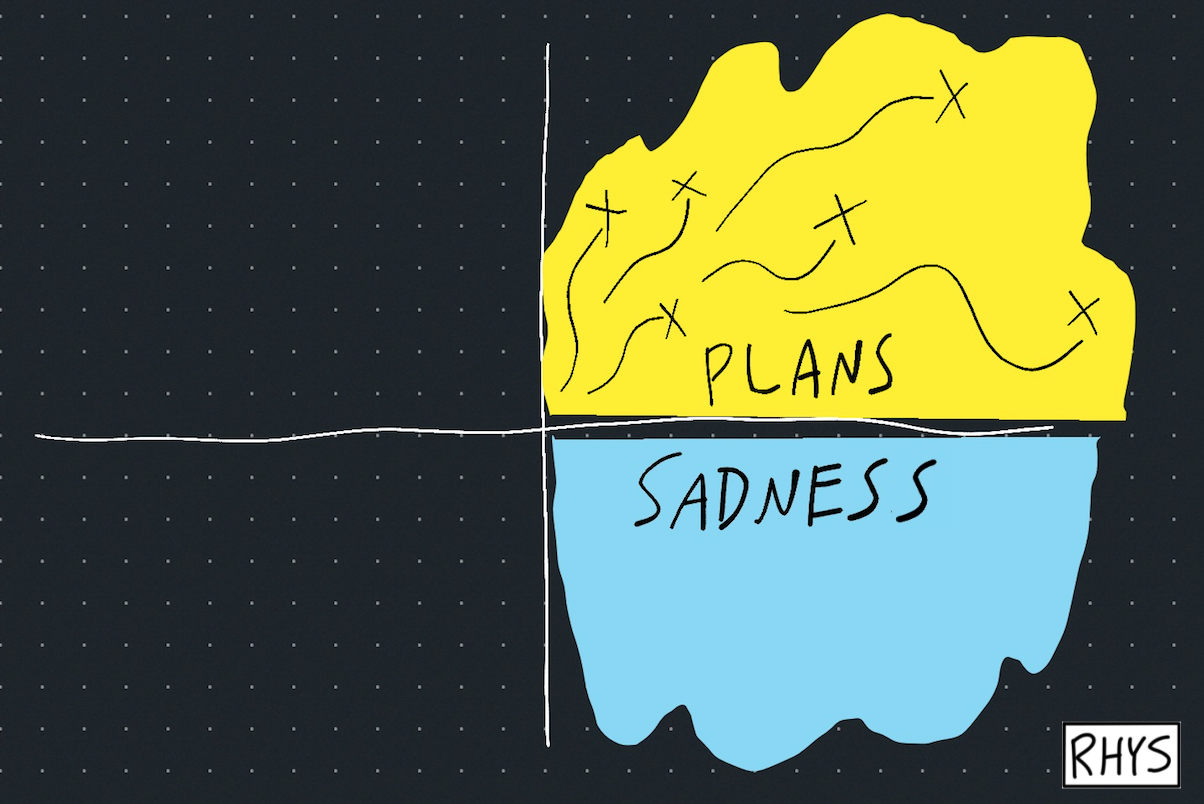

Sadness is loss. This can be a loss of the past (memories) or a loss of the future (plans).

This blue sadness is the reverse of the yellow memories/plans. It is the "hole" that people speak of. And it's why its especially sad if you lose someone close to you. The hole/loss is bigger.

This is represented in the quote: "Sadness is the price we pay for love.” If you have +y memories/plans, you will have -y sadness.

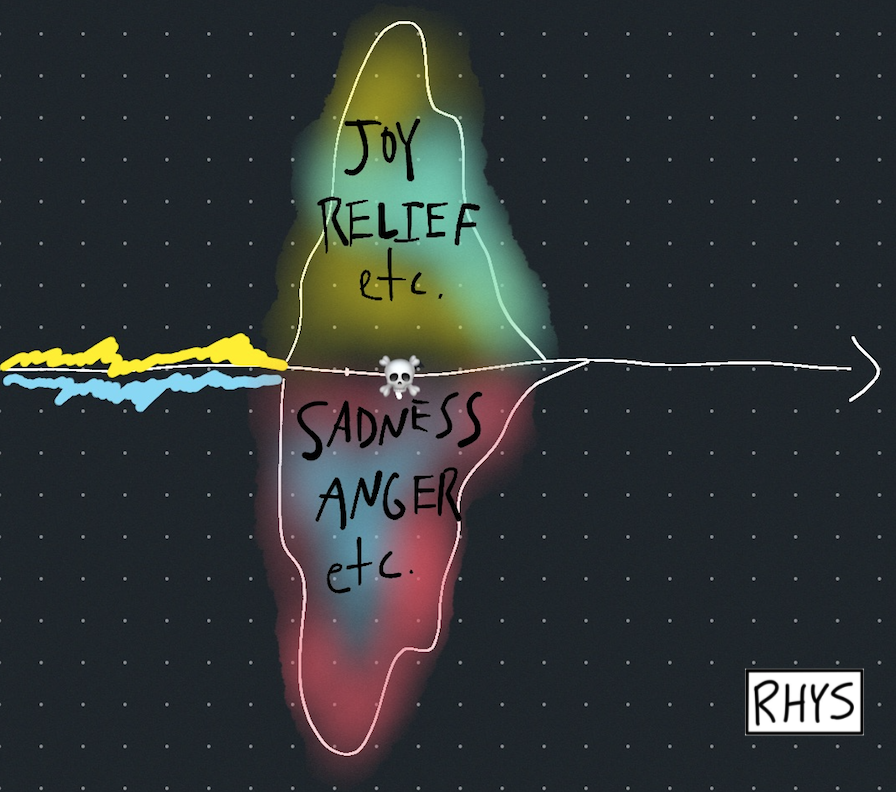

Grief is Complex: It is Full of Sadness and Many Other Things

Grief is a bit different than "pure" sadness. It's more about the holistic relationship to the dead person and to death itself. Because of this, grief is not just sadness—it's full of many other things too. As my friend wrote to me when my mom passed:

That is such a major life event. I'm sure it's full of so much emotion and non-emotion, and many other things too.

When your mom dies, life just becomes more. More sad, more happy, more logistics, more reflective. More.

Grief is not just one thing. As Nora McInerny says here, "grief is a multi-tasking emotion".

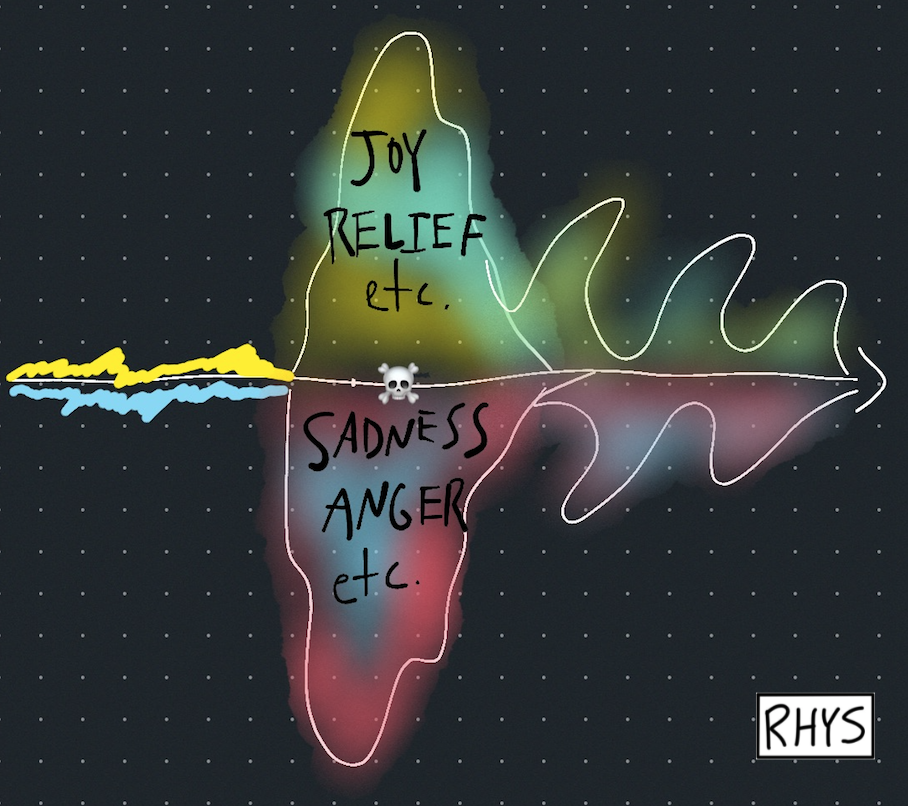

Grief Happens Over Time: As a Waves, Not a Staircase

But grief is not a one-shot event. It happens over time.

In popular culture, this is usually expressed through the staircase metaphor and the 5-stage Kübler-Ross model: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Unfortunately, this model isn't supported by empirical evidence. It's similar to Myers-Briggs—a unsubstantiated model that is being hawked by a company (who trademarked the Five Stages of Grief™ and bought the grief.com domain name!).

Modern models of grief are more complex: more like a rollercoaster/waves and less like a staircase. After my mom died, a friend used the wave metaphor:

I have found it a good reminder that during times of extreme grief, we can hold onto hope of the waves becoming less frequent and smaller one day. And also just as importantly, that when you’re having times that aren’t as hard (or even dare I say, good) to know that that too, is ok.

I've found this metaphor to be freeing. Instead of saying "you should go through these 5 stages in this order", this model says "everyone has their own experience with grief. Being sad is ok. Being happy is ok. It will change." There's no universal method for healing.

III. Three Paradoxes of Grief

As I came to understand grief, I also discovered some paradoxes of grief and death. Here are three:

Paradox #1: Keep The Dead but also Let Them Go

The first paradox of grief is:

- The dead are alive. Keep them with you in memories.

- The dead are dead. Let them go.

The first point is—the dead are alive! This is final point in my mom's eulogy: that her language (and way of perceiving the world) will stay with me, even after her death.

Here are some nice quotes on how the dead stay with us:

"They say you die twice. One time when you stop breathing and a second time, a bit later on, when somebody says your name for the last time." — Banksy

"No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away." — Terry Pratchett

"What we have once enjoyed deeply we can never lose. All that we love deeply becomes a part of us." — Helen Keller

"The bad news is that you never completely get over the loss of your beloved. But this is also the good news. They live forever in your broken heart that doesn’t seal back up. It’s like having a broken leg that never heals perfectly—that still hurts when the weather gets cold, but you learn to dance with the limp." ― Anne Lamott

So, the first point is—the dead are alive and stay with us. But the second point is—the dead are dead! We should learn to let them go. When my mom died, a friend sent me this poem from Mary Oliver, "In Blackwater Woods". Here's the conclusion:

you must be able to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.

Paradox #2: Death is Personal AND Universal

The second paradox is:

- Death is an immensely personal experience. Your mom will die.

- Death is an immensely universal experience. Everyone has a mom. She will die.

Every person is unique. But death is not. Everyone dies. (This is nice because it allows us to connect with anyone about death.)

Paradox #3: Death Gives Life Meaning and Destroys It

The third paradox is:

- Death gives life meaning.

- Death destroys life and meaning.

Without death, life would be an ambiguous, continuous, meaningless state of simple existence. By making time scarce, death gives meaning to life.

And yet, death destroys the whole thing. When there is no brain to process this gifted meaning, what was the meaning for?

I hope these paradoxes and visuals of grief helped you understand it better, whenever it comes to you.

Now, let's move away from the (more personal) death of my mother to the (more public) deaths of George Floyd and COVID patients.

IV. The Homicide of George Floyd

George Floyd died a week after my mother.

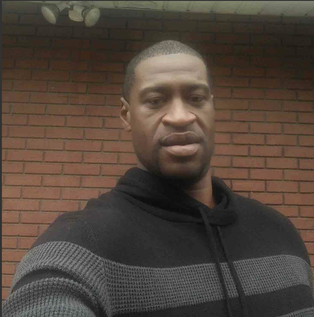

I'm sad. Just like with my mom, looking at his face makes me cry.

With my mom, it was "easier" to feel sadness because I had so many memories of her. With George, I can actively try to learn about his memories. More empathy helps me feel more sad. Here's a bit on George's life, from Wikipedia:

George Floyd was a star tight end for Yates, helping them to the 1992 state championship final game. Floyd joined the hip hop group Screwed Up Click and rapped under the stage name "Big Floyd", after entering the Houston Hip Hop cultural scene as an automotive customizer. In 2014, Floyd moved to Minnesota. He lived in St. Louis Park and worked in nearby Minneapolis as a restaurant security guard for five years, but lost his job due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Floyd was the father of two daughters, ages 6 and 22, who remained in Houston.

His cousin, Tera Brown, criticized the police, saying, "They were supposed to be there to serve and to protect and I didn't see a single one of them lift a finger to do anything to help while he was begging for his life."

One of his brothers echoed the sentiment, saying, "They could have tased him; they could have maced him. Instead, they put their knee in his neck and just sat on him and then carried on. They treated him worse than they treat animals."

Floyd's uncle, Selwyn Jones, said: "The thing that disturbs me the most is hearing him call for my sister."

Learning about George's past memories and future plans helps me feel sad about his death.

We can use the same images from above to represent our sadness for George.

And also our multi-dimensional grief:

I want to explore two quick concepts related to George Floyd: oppression, and violence.

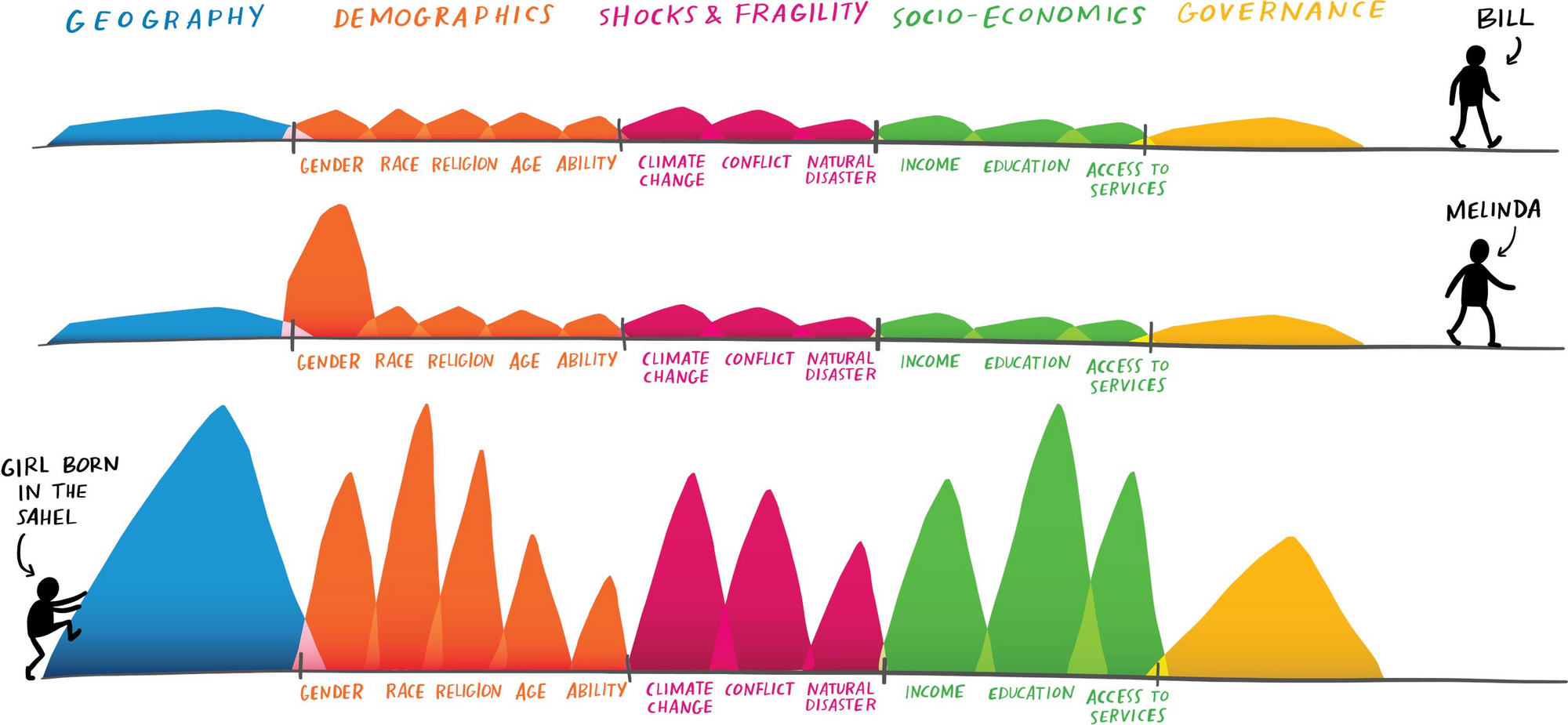

#1: "Experiential Space-Time" Helps Us Understand the Daily Experience of Oppression

"Experiential space-time" is the idea that the world is full of unique lived experiences. You can do it for individuals, but also zoom out for humanity as a whole:

- For individuals, every day is full of so much "experience". You wake up, eat three meals, work, hangout with friends, etc. Every day is so full! And that fullness happens 365 days a year for around 80 years. That's a lot of "experiential space-time".

- AND, there's all of the 7.6 billion other people out there. Each with their own experiences. The "experiential space-time" of one person times 7.6 billion people. That's a lot!

- Plus, all of the 100 billion people that have already lived and the trillions that will live. There's a lot of human experience (aka "experiential space-time") that has already happened, is currently happening, and will happen.

I like to use the concept of "experiential space-time" in two main scenarios:

- When I'm trying to understand a single person's experience (and see that wow, they have SO MUCH life that I can't even begin to understand it).

- When I'm trying to conceptualize of the massiveness of all human experience (and see that wow, it's so large! I probably don't matter much).

Experiential space-time is a helpful way to understand the lived experience of oppressed folks. It may not seem "so bad" when you think about a couple of one-off experiences for them. But it's not just a single experience. It's a daily, constant, omnipresent experience of being perceived as lesser. As Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote:

African Americans have been living in a burning building for many years, choking on the smoke as the flames burn closer and closer. Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible — even if you’re choking on it — until you let the sun in. Then you see it’s everywhere. As long as we keep shining that light, we have a chance of cleaning it wherever it lands. But we have to stay vigilant, because it’s always still in the air.

Or, in Obama's statement:

We have to remember that for millions of Americans, being treated differently on account of race is tragically, painfully, maddeningly "normal" — whether it's while dealing with the health care system, or interacting with the criminal justice system, or jogging down the street, or just watching birds in a park.

Or, in Hilary Clinton's story of taking the LSAT as a woman in the 1960s:

I was taking a law school admissions test in a big classroom at Harvard. My friend and I were some of the only women in the room. I was feeling nervous. I was a senior in college. I wasn’t sure how well I’d do. And while we’re waiting for the exam to start, a group of men began to yell things like: ‘You don’t need to be here.’ And ‘There’s plenty else you can do.’ It turned into a real ‘pile on.’ One of them even said: ‘If you take my spot, I’ll get drafted, and I’ll go to Vietnam, and I'll die.’ And they weren’t kidding around. It was intense. It got very personal.

Or, the reverse, white privilege as the absence of what Abdul-Jabbar calls "dust in the air", and the presence of systems that provide privilege. As Peggy McIntosh writes in White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack:

"Racism is not individual acts of meanness, but is invisible systems conferring dominance on my group."

This image from the Gates Foundation gets at a very similar concept. Bill and Melinda had very few hills to climb, while a girl in the Sahel has an immense amount of climbing to do.

Whether you use hills, dust in the air or another metaphor, oppression is a constant, daily experience that I try to understand better by imagining the "experiential space-time" of marginalized groups.

#2: Hurt People Hurt People

The second concept that I want to highlight is "hurt people hurt people". That is, people who are experiencing pain end up damaging others.

This reinforcing feedback loop (hurt people hurt people) happens at two levels.

First, at the macro police/protester level: Escalating force by police leads to more violence, not less, and tends to create feedback loops, where protesters escalate against police, police escalate even further, and both sides become increasingly angry and afraid.

It also happens at the individual level. George Floyd was hurt (lost his job due to COVID), then (allegedly) used a counterfeit $20 bill. Or, on the officer's side: What childhood "hurt" does Derek Chauvin have that made him ignore Floyd's suffering?

Here's a simple visualization of this reinforcing feedback loop:

However, like any reinforcing feedback loop, it IS possible to escape it and enter the opposite feedback loop: loved people love people.

As Floyd's girlfriend said: "You can't fight fire with fire. Everything just burns, and I've seen it all day – people hate, they're hating, they're hating, they're mad. And he would not want that."

Or Floyd's brother, Philonese, who called for peace and said, "Everybody has a lot of pain right now, that's why this is happening, I'm tired of seeing black people dying."

See my favorite Tara Brach quote (on how to respond to anger):

Love begets love. Hate begets hate.

I hope it's possible that we can: a) Use experiential space-time to empathize with the sadness of death and the daily experience of oppression. And b) Understand that hurt people hurt people, so we should try to get to a place where loved people love people.

[Note: This section was mostly me processing grief and understanding oppression. For specific places to donate, see this list or this amazing thread of research-based solutions to police violence. I have donated to the National Council.]

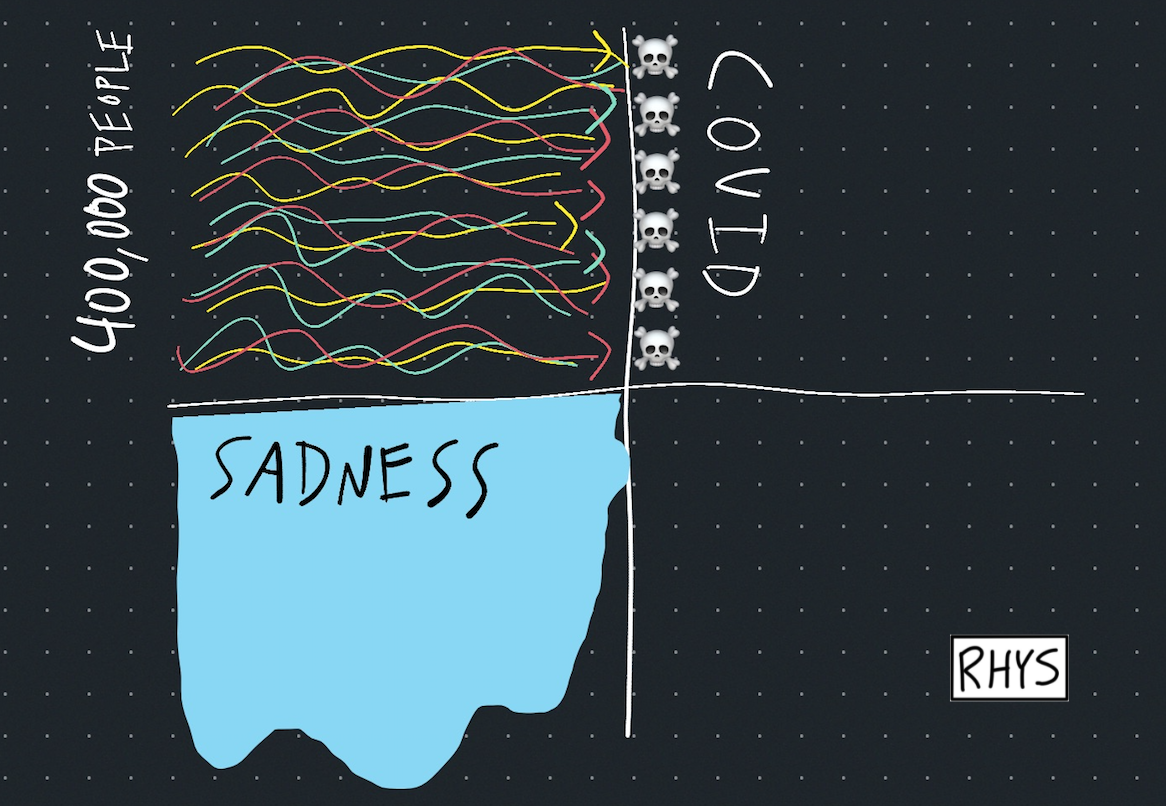

V. The Communal Grief of COVID

Finally, we're also experiencing the communal grief of COVID deaths—nearly 400,000 people thus far. This powerful New York Times front page humanizes the 100,000 deaths in the US: They Were Not Simply Names on a List. They Were Us.

There's grieving the individuals who have lost their lives:

And there's the (lesser) sadness for the rest of us—our lost plans in the next 12 months. For me, this was moving to San Francisco with dreams of, well, interacting with people at all 🙂.

Conclusion

I wish things weren't like this. I wish that we treated Alzheimer's better (and my mom didn't die). I wish that race relations and policing were better (and George Floyd didn't die). I wish that our COVID response was better (and 400,000 people didn't die).

But they weren't.

We should keep their memories with us. And also, we should let them go.

Let's keep relentlessly striving for progress while acknowledging that we cannot change the past.

...

Grief is complex. I hope this article helps you process it.

Thanks for reading. As always, I'd love your feedback in a comment below or over email.

Love you, Mom. ❤️

Related Articles

- For more on BLM, see: The Remixability of Hashtags, #_____LivesMatter, and #FutureLivesMatter

- For more on paradoxes, see: Attachment vs. Non-attachment.

Additional Notes

Mom and Grief

- Saying that grief is different for everyone and comes in waves is kind of like saying everything and nothing at all. You're saying "you will experience life and will continue to experience life". A vapid framing. Yet one that I still found helpful. Interesting!

- In line with the waves framing, I like this from Nora McInerny: "We don't "move on" from grief. We move forward with it."

- Modern models of grief align with the [waves/everyone is different/you don't need to be sad] framing. 50% of people respond to death with "resilience". Also: Bonanno's work has also demonstrated that absence of grief or trauma symptoms is a healthy outcome, rather than something to be feared as has been the thought and practice until his research.

- I don't know why, but crying about my mom's death is especially triggered by either: a) Looking at pictures of her (usually alone). Or b) When other people share nice things about her.

- I like the perspective that one can become an orphan after their parent dies. I know I'm not like a "real" orphan. But it was a helpful frame.

- I had a lot of ambiguous loss before my mom passed away. Again, this was a super helpful framing. It's loss that hasn't fully happened (my mom was not herself, but she wasn't dead). So you can't feel "resolved" with it. I feel much more resolved now.

- Related: My family felt a lot of relief after my mom died. Is relief an emotion? I guess "peaceful" is an emotion. (Acceptance.)

- Related: Although my mom's death was super expected, it was still surprising and really really sad. So final. I'm not quite sure I understand this side of things. As Lemony Snicket wrote: “It is a curious thing, the death of a loved one. We all know that our time in this world is limited, and that eventually all of us will end up underneath some sheet, never to wake up. And yet it is always a surprise when it happens to someone we know. It is like walking up the stairs to your bedroom in the dark, and thinking there is one more stair than there is. Your foot falls down, through the air, and there is a sickly moment of dark surprise as you try and readjust the way you thought of things.”

- The "keep close" and "let go" paradox is expressed in attachment vs. non-attachment as well. Vajrayana Buddhism ftw :).

- Optimistic Nihilism is also super connected to the "keep close" and "let go" paradox.

- A paradox that I didn't include above: death makes us feel super connected and also super alone. From Hunter S. Thompson: “We are all alone, born alone, die alone, and—in spite of True Romance magazines—we shall all someday look back on our lives and see that, in spite of our company, we were alone the whole way. I do not say lonely—at least, not all the time—but essentially, and finally, alone.”

- Although it was helpful for many people, I'm sad that this HBR article uses the 5-stage model for grief: The Discomfort You're Feeling Is Grief.

- "The Dead Stay With Us" is the foundation of the Pixar movie, Coco. Here's the premise: When you die, you go to an "afterlife". But you're only alive in the afterlife if you're still remembered in the real world (on Dia de los Muertos). Once you're forgotten in the world, you pass from the afterlife too. Memories of the dead keep them alive.

George Floyd

- As a rich, white, straight, American man, I know I'm generally supposed to listen. Did I do something wrong here (by writing this piece)? Am I appropriating this cultural and COVID moment?

- It's interesting that my mom's death felt like it gave me more...space to speak as a white man.

- I tried to pay attention to my language here. e.g. Writing "homicide" instead of "death" for the Floyd's section header. Wikipedia's page was initially "Death of George Floyd" but is now "Killing of George Floyd".

- I was tempted to add a page of white (black?) space and encourage a moment of silence. But it didn't feel right.

- To the experiential space-time section, I wanted to add all the BLM deaths. (This image and this image.)

- Feedback loops are so powerful. Power begets power. Hurt People Hurt People. Whenever there's a bad reinforcing feedback loop, I'm a huge fan of overcorrecting. You won't actually overcorrect because you're fighting a feedback loop. So aim for something crazy, then fall way short. (e.g. This is why I'm generally in favor of goals like F500 CEOs should be 2x rate of marginalized population.)

- I like how Obama's other statement actively discusses how norms turn into laws. (Lessig's dot and theory of change stuff!)

- On Hurt People Hurt People: In nonviolent communication, we often say "anger is the result of unmet needs".

- This idea (to get in a positive feedback loop where "loved people love people") is roughly the same as "egoistic altruism" as explained by Kurzgezat and "endogenous growth theory" as explained by Paul Romer.

- The ideas in Center for Paradigm Change hope to create a world without violence, but also ignore violence (too much) as a result.

- All of the language that is used for the [lived experience/experiential space-time] section is paradigmatic. The experience of living as a black man is America is not about a specific law or norm or whatever. No, it's the "Water They're In". M. Holston-Alexander explicitly states this in her piece here: "racism was in the water I drank as a child."

- I didn't push this too much, but I am interested in trying to empathize with Derek Chauvin. I know its controversial, but I do think relentless empathy (and then solving root cause problems) is "the way out". For example, Chauvin must be feeling like shit right now (and for good reason). His wife just left him: The wife of Derek Chauvin, the officer who knelt on Floyd's neck, filed for divorce and offered her condolences to the Floyd family.

- It reminds me of this empathizing scene in (the amazing movie) Blindspotting. In that scene we see how destroyed the white cop is after an incident like this.

- And this amazing I'm Not Racist music video from Joyner Lucas.

COVID

- I wanted to add a piece about how hungry people went from 800M to 1.6B (from COVID), but couldn't find the space.

- Beyond the NYT page, what else has humanized COVID?